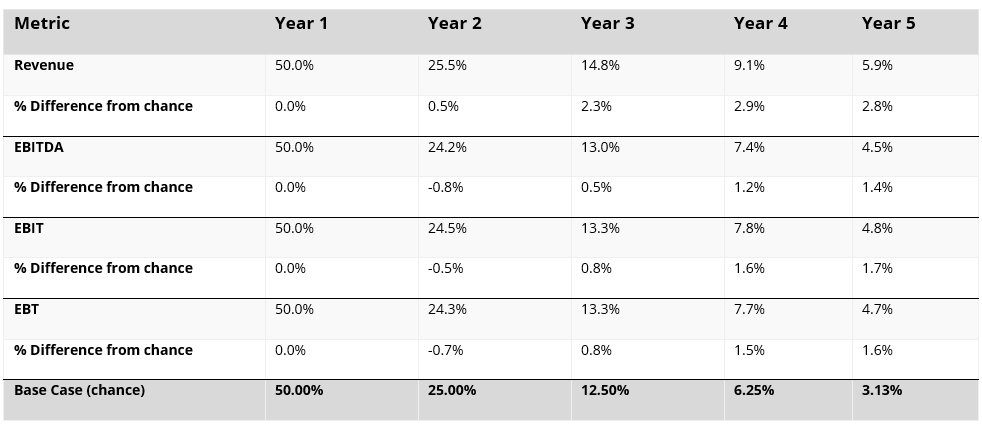

It’s worth saying from the start that my entire investment philosophy is based on a belief that the average investor suffers from behavioural biases such as over-confidence, extrapolation and herding. When growth is high (for a company, industry or whole market) investors tend to assume it will stay high, putting a high valuation on high earnings. Since very few companies can grow earnings at an above average rate for an extended period (see Chart 1 below), high expectations are likely to be disappointed, which usually results in poor returns from the stock, sector, or market in question.

Chart 1: Persistence of Growth Rates (1997-2021)

The opposite is also true. Where earnings have been lacklustre, the average investor assumes they will remain this way, thus setting a lower bar of expectation. It also means that the risks are usually to the upside. I covered this to a certain extent in my recent blog on the folly of forecasting.

Let’s look at the topic of US equity valuations with these principles in mind.

1. Have US equities delivered a higher rate of growth than international equities?

A recent paper from GMO looked at this question and concluded that US equities have enjoyed faster earnings growth than their international peers.

‘U.S. stocks did deliver on fundamental returns, though. That is, their non-valuation sources of returns – dividends, share repurchases, and organic growth – outdid the non-valuation sources of returns in the rest of developed markets. Given that U.S. companies are more expensive than their DM peers, this mostly implies that U.S. businesses outgrew their international competitors. And this is probably why so many investors are happy to have most of their money in U.S. equities. They expect the fundamental outperformance (and particularly the fundamental growth) of the past to repeat; they think the companies of the future are [listed] American businesses.’

As investors, however, we must look forward not backwards and ask ourselves how likely this is to continue. The paper suggests this excess growth is in the past.

‘If we start the clock in December 2014 instead of December 2010, the U.S. fundamentally outperformed the rest of the developed markets by a smidge: an aggregate 3.8%. Fast-forward to December 2019, and the fundamental outperformance since then is nil. Any additional growth that U.S. companies were able to muster was simply not impressive enough to out-return their international peers.’

So right now, it would appear investors are paying a massive premium for US equities despite no additional growth.

2. What was the source of the additional growth and is it sustainable?

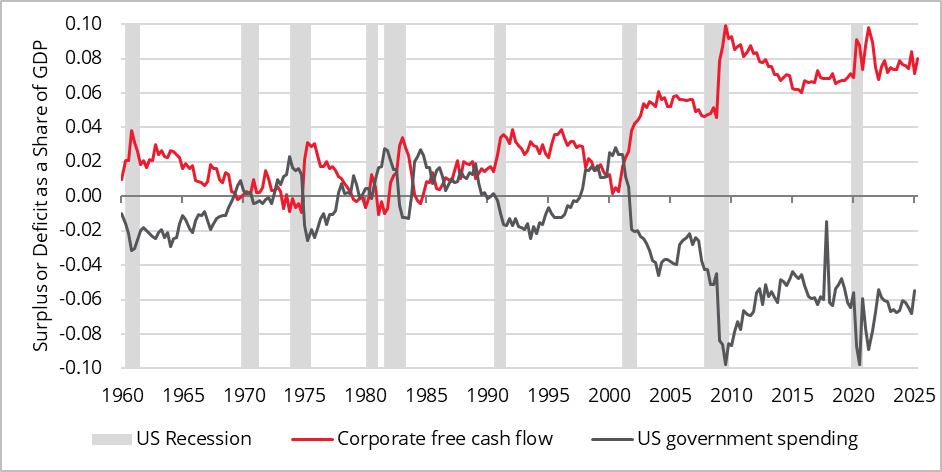

Probably the largest source of excess US earnings was the enormous deficit run by the US government. This is discussed in a paper by John Hussman in which he makes the following point:

‘Specifically, as government deficits exploded in recent years – particularly resulting from a combination of tax cuts and pandemic spending – corporate free cash flows also exploded. They had to. This wasn’t because of some new-era productivity boom. It was because of equilibrium. It’s just an accounting identity. But it creates a situation where perpetually extreme corporate earnings now rely on perpetually extreme government deficits. They are mirror images of each other.’

So here I think investors must question whether the US can run this size of deficit forever (I suspect not). And, even if they can, is this not likely to have implications for bond yields, the US dollar and the inflation rate, all of which are likely to be negative for corporate profitability and the valuation of US equities? Even the most optimistic investors must admit the risks to the downside on the sustainability of US corporate profits.

3. To what extent is the excess growth concentrated in the large technology companies, is that sustainable and is it already priced in?

Again, the GMO paper addresses this issue and finds that the median US company is now doing worse than the median international company.

‘The median fundamental return for a stock in the S&P 500 (ex-financials) over the five years ending in December 2024 was an annualized 4.0%, which is lower than it is for any other five-year increment since the mid-80s, including the mediocre cycles ending in 1994 (5.2%) and 2004 (4.1%). A full 60% of the companies in the S&P 500 were unable to reach the “old norm” fundamental return of 6% real. The best that can be said of the recent period is that the companies that did the worst over the last five years did somewhat less badly than usual for underperformers.’

In other words, the historic excess growth has been concentrated in the big technology stocks, so investors in US equities must ask themselves if this is sustainable and what is priced in given that they are a third of the index[1]. In our view, valuations imply that the growth rates are going to continue at a time when they are making an enormous bet on AI. Not only does this increase the risks around future earnings (there is no sign yet that this investment is going to make a decent return) but it fundamentally changes the business model of these companies. Historically, their high valuations were ‘justified’ by their capital light model, and this is no longer the case given the colossal investment going into AI. All other things being equal, this should lead to a derating.

One of the best discussions I have read on this issue is by Harris ‘Kuppy’ Kupperman. Given that I was a telecoms analyst in 2000, the tech companies throwing hundreds of billions at AI reminds me of what telcos did back then (and which ended up being great for consumers and terrible for shareholders).

4. Is this time different?

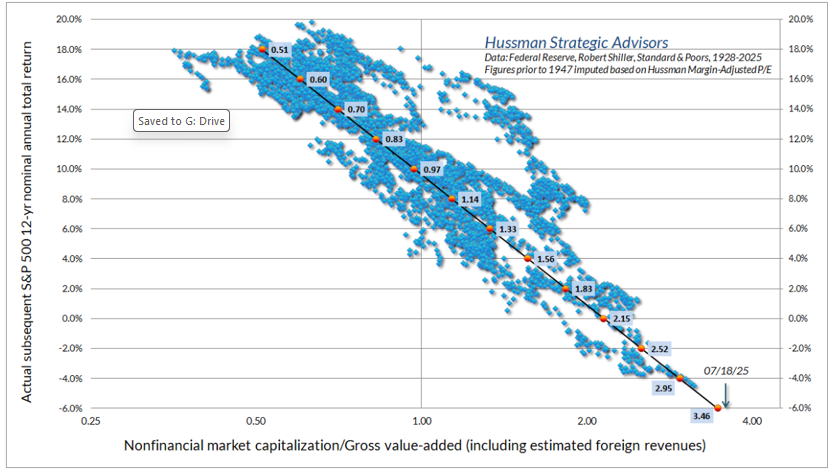

Even if we ignore all the above and say that US equities can go back to growing at a growth rate above their international peers, we always need to bring this back to valuation and ask if that outcome is already priced in. Here, I believe, Chart 3 below from another piece by John Hussman is extremely useful. It maps valuation of US equities across the x-axis against the subsequent 12-year annualised return from when you bought the market on those valuations on the y-axis. I would make the following points:

I. Note this is nearly 100 years of data and thus statistically significant

II. It is a near perfect (negative) correlation with an R-squared of -0.93

III. The US market today is trading on the highest valuation that has been observed in these hundred years of data (bottom right on the chart)

IV. If the correlation holds, investors in US equities should expect to lose 6% p.a. for the next twelve years. A big exposure to US equities today is literally a bet that ‘this time is different’.

Chart 3: S&P500 valuations and subsequent 12-year returns

In summary, I believe that the arguments for some diversification from US to International Equities are compelling and, whilst the move has already started with the EAFE index significantly outperforming S&P500 year to date [2], I think this is only the start of a multiyear rotation.

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to the future. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.

Sources:

[1] Bloomberg, 2 September 2025

[2] Bloomberg, 2 September 2025