As interest rates in the US, Europe, the UK and Brazil appear to have peaked, we examine how the global listed utilities sector could behave if these interest rates were to come down.

It has long been considered that the dynamics of interest rates and yield curves were the primary drivers of sector performance. Investors keenly watched these indicators as signals about the economic cycle and appropriate portfolio positioning: risk-on vs. risk-off. However, times have changed as utilities have more growth than before, notably through the development of non-regulated activities, and considering them only as bond proxies is less appropriate as the sector evolves. In addition, many utilities now include inflation pass-through mechanisms in their regulated frameworks or deregulated contracts (eg. in wind and solar power purchase agreements (PPAs).

Although interest rates remain important for capital-intensive companies and lower interest rates would be an undeniable tailwind for the sector, notably due to asset allocation flows, we believe there are now other factors/drivers of performance – and relative performance in particular.

Key takeaways

- Plateauing or declining interest rates typically create a more favourable environment for utility companies, influencing cash flow discounting and financing costs, dividend appeal, and investor sentiment

- Active management can leverage rate-driven dislocations within utilities (both across and within sub-sectors) to enhance returns and reduce risk through active positioning

- Once seen as mere defensive bond proxies, utilities are now exposed to structural growth trends underpinned by electrification, surging power demand and the explosive growth of data centres

Why do utilities benefit from lower rates?

Lower interest rates can create a more favourable environment for utility companies, influencing everything from financing costs to investor appeal. As borrowing becomes cheaper, utilities often find new opportunities to refinance debt on favourable terms, strengthen balance sheets, and invest in new infrastructure at a lower cost – topics explored in greater depth below.

Cash flow discounting: regulated utility companies are rate-sensitive because declining interest rates decrease their cost of capital and increase the present value of long-term cash flows.

Lower borrowing costs: utilities are typically highly capital-intensive, meaning they borrow significant amounts of debt to fund long-duration infrastructure investments such as power lines or water networks. Lower interest rates reduce their borrowing costs, which in turn leads to improved earnings and returns.

Increased dividend appeal: utilities tend to be seen as bond proxies due to their relatively stable and visible contracted and regulated revenue streams, often translating into dividend payments. When interest rates fall, bonds become less attractive, causing investors to shift into higher-yielding utilities, which drives stock prices higher.

Improved risk-reward profile: lower rates combined with the structural trends such as the electrification of the economy, grid modernisation and renewable energy investments make utility stocks compelling alternatives to fixed income products.

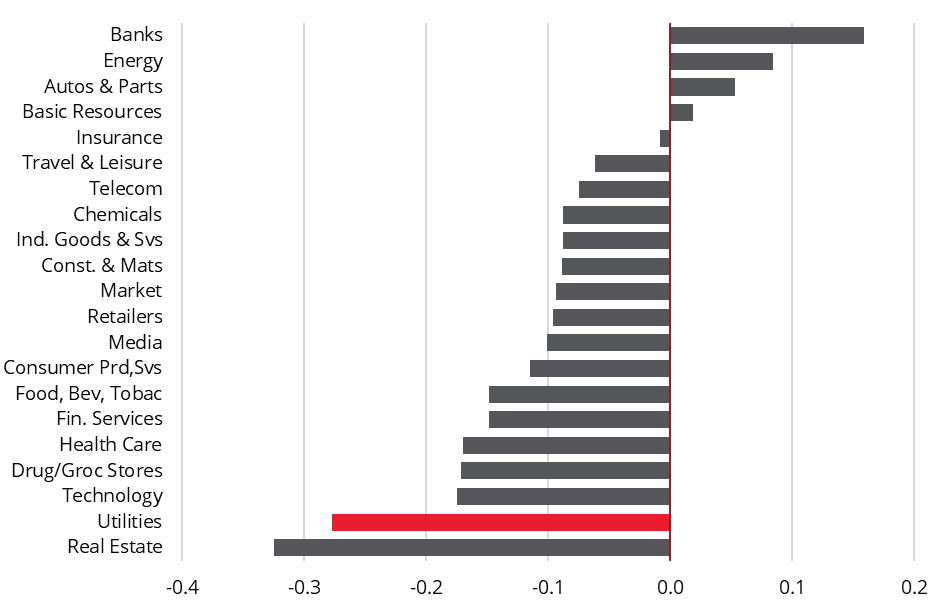

Chart 1 illustrates the inverse relationship between utilities and rates. Based on 5-year correlations, the European utilities sector (SX6P index) has the second-highest negative relationship to German 10-year bond yields, following real estate which is often viewed as another defensive bond-like investment.

Chart 1: Utility stocks show the second-highest negative correlation to bond yields

European utility stocks are most sensitive to rates during regime changes

Utilities are particularly sensitive to large swings in interest rates as these regime changes abruptly shift their borrowing costs, disrupting their medium-term financial planning and expected return on capital.

While some utility companies are able to pass through the impact of higher interest rates – automatically in some regulatory jurisdictions or indirectly via higher PPA prices – there is nonetheless a potential negative timing impact on cash flows. In addition, some projects (especially in renewables) have lengthy durations and returns can become uneconomical when rates jump sharply in a relatively short period of time. Smaller and more progressive rate changes typically allow for gradual adjustment, but big hikes sharply elevate the weighted average cost of capital (WACC), compressing returns, and in some cases forcing delays or cancellations of capital-intensive investments.

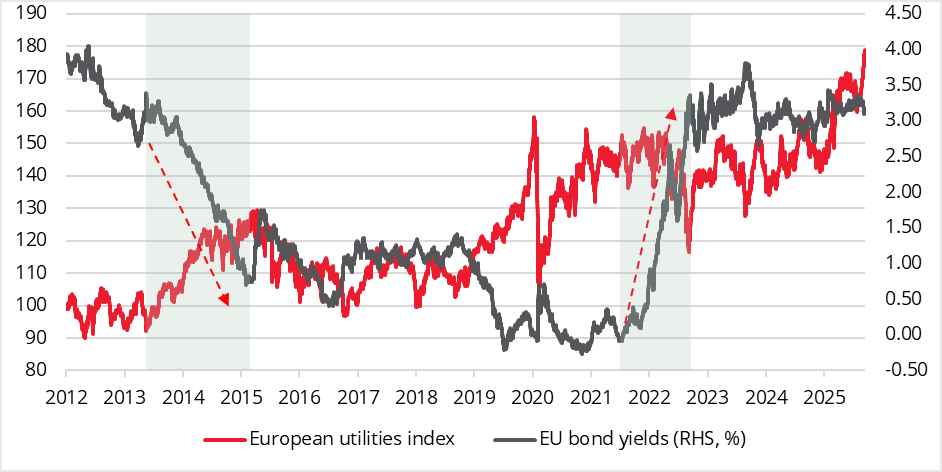

To illustrate this point, we take a closer look at the two main rate regime changes which took place in Europe over the last 15 years below: the 2013-15 easing cycle and the 2021-22 tightening cycle.

2013-2015 easing cycle: Eurozone interest rates plunged to historic lows as the ECB fought to revive a fragile post-crisis economy. The region was still reeling from the sovereign debt turmoil with weak growth, record unemployment and dangerously low inflation. To counter this stagnation, the ECB embarked on an unprecedented wave of monetary easing measures which resulted in a >250bps decrease in bond yields. Utilities performed well during this period, with the European utilities benchmark up >35% [1].

2021-2022 tightening cycle: interest rates across the European Union surged at an unprecedented pace between 2021-23, as policymakers scrambled to contain runaway inflation. After years of ultra-loose monetary policy, the post-pandemic rebound collided with supply chain disruptions, soaring energy costs and the economic fallout from the invasion of Ukraine – all of which sent prices surging. Soaring inflation forced the ECB to pivot sharply from stimulus to restraint and deliver a series of aggressive rate hikes. Higher rates combined with spiralling inflation put growth prospects of many companies into question. This also put project-level returns under pressure and resulted in material valuation multiple compression. Utilities clearly struggled (-21%) as rates increased by >300bps over the period [2].

These two examples clearly demonstrate that the inverse correlation between utilities’ performance and rates is much higher when we are witnessing a regime change rather than modest moves within a range.

Chart 2: European utilities are most sensitive to rates during regime changes

Not all utilities are created equal: intra-sector disparities

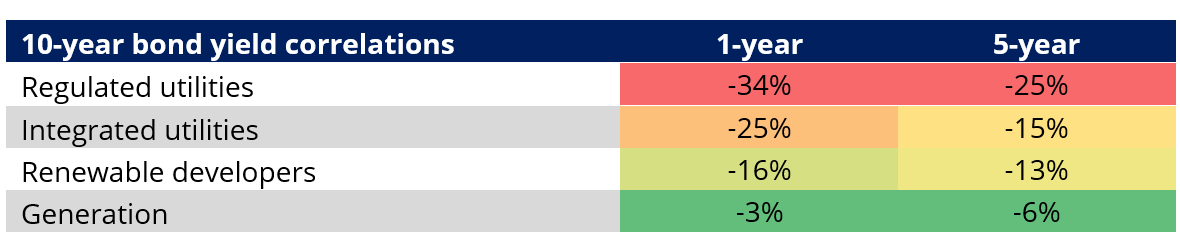

Not all corners of the utilities sector move in lockstep when interest rates rise or fall. The correlation can vary sharply across (and to some extent within) sub-sectors because each has its own mix of regulatory environment, capital intensity and exposure to market forces.

- Traditional regulated electric and gas utilities tend to have the highest negative correlation to rate moves as their high debt levels make financing more expensive, and their steady dividends look less attractive compared with higher bond yields.

- Integrated utilities typically operate a combination of regulated transmission & distribution assets, generation and retail. As such, these companies also tend to have elevated gearing levels and are sensitive to rate moves.

- Renewable energy companies mostly feel rate shifts through the project-financing channel as higher borrowing costs can delay new developments and compress valuations built on long-term discounted cash flows.

- Generation companies are typically well-established, low growth businesses with strong balance sheets and are therefore much less correlated to rate moves. By contrast, these names tend to be much more sensitive to commodity prices (eg. gas, coal).

1-year and 5-year correlations summarised in exhibit 3 below illustrate these intra-sector disparities.

Chart 3: European regulated and integrated utilities have the highest rates sensitivity

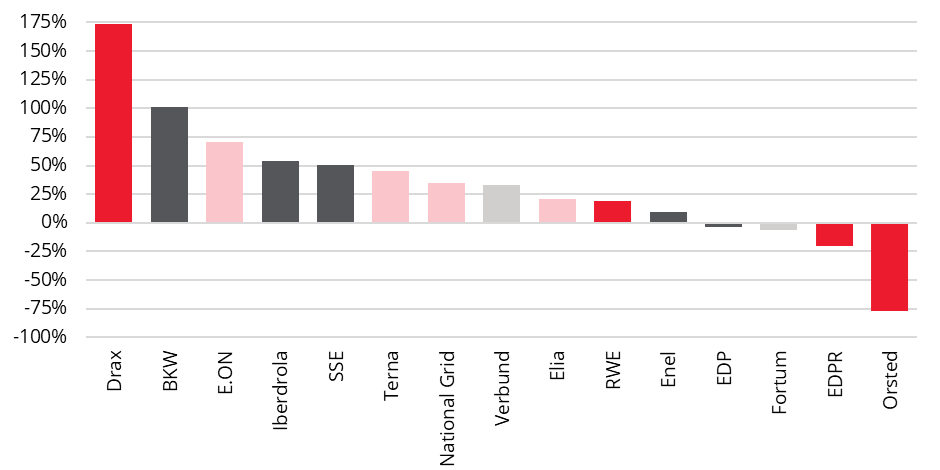

Even within a single sub-sector, individual stocks can display markedly different correlations to interest rates, reflecting the nuances of their business models, capital structures and market positioning. Two regulated electric utilities may both rely on steady cash flows, but one with heavier debt, more floating rate debt or short maturity, or aggressive dividend policies will be more sensitive to rising rates than a more conservatively financed peer. Similarly, renewable energy firms with long-term PPAs may react differently depending on the mix of government incentives, inflation-adjusting contracts, and geographic exposure. Factors such as contract length, regulatory environment, leverage and exposure to commodity prices shape how each company responds to interest rate moves.

Chart 4: Despite clear trends at sub-sector levels, intra-sector dispersion is high

US vs. European utilities: (mostly) similar patterns across the pond

US utilities, much like their European counterparts, exhibit a pronounced sensitivity to interest rate movements. With their business models built on long-term, regulated cash flows and capital-intensive infrastructure, higher rates raise the cost of debt and reduce the present value of future earnings. In an environment of low interest rates, these companies typically become particularly attractive to income-seeking investors, offering steady dividends and defensive stability that mirror bond-like characteristics.

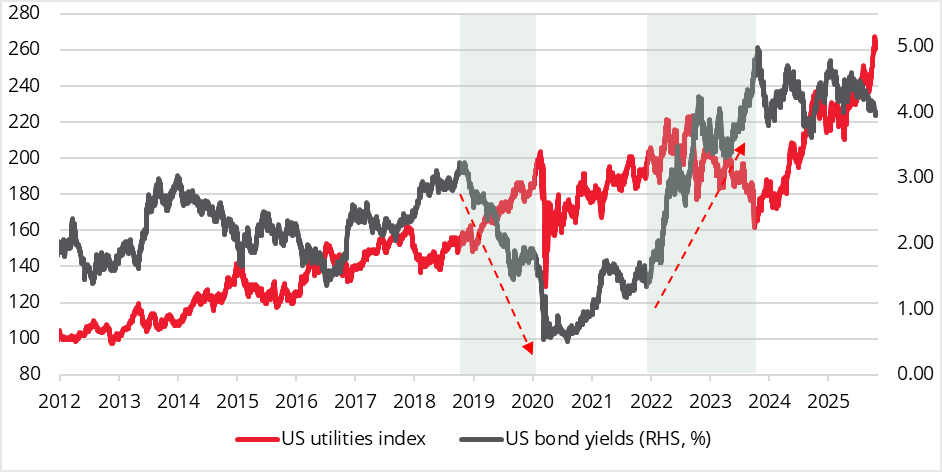

We repeat the exercise we have done for Europe and take a closer look at the two main regime changes which took place in the US over the last 15 years below: the 2018-20 easing cycle and the 2021-23 tightening cycle.

2018-2020 easing cycle: The 2018-20 US rate easing cycle marked a sharp Fed pivot from tightening to stimulus. After raising rates steadily through 2018, policymakers reversed course in 2019 with three precautionary cuts to buffer trade tensions and slowing global growth. The shift turned dramatic in early 2020 as the COVID-19 shock forced emergency action and rates were slashed to near zero. US utilities rallied 30% while rates decreased by >165bps over that period (excluding the impact of the COVID crisis) [3].

2021-2023 tightening cycle: This was one of the Fed’s most aggressive tightening cycles in decades, aimed at reigning on inflation that surged after the pandemic stimulus boom. The Fed pivoted in March 2022, delivering 11 hikes in just 17 months to lift its funds rate above 5%. In this challenging context, rates increased by >300bps and US utilities sold off by 20% over the period [4].

Chart 5: US utilities are also most sensitive to rates during regime changes

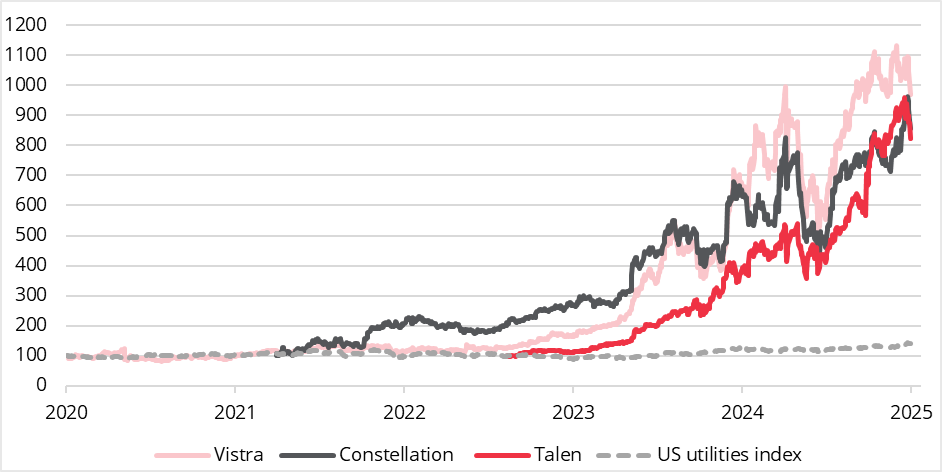

However, not all US utilities fit the classic interest rate-sensitive profile. Independent power producers (IPPs) like Vistra, Constellation and Talen have largely bucked the trend, thanks to lower leverage and strong free cash flow generation. These companies have also been beneficiaries of the “nuclear renaissance” and the surging power demand from data centres and other digital infrastructure. With robust earnings growth and less reliance on debt financing, IPPs are likely to withstand monetary tightening more effectively, highlighting the nuanced diversity within the US utilities landscape – similar to Europe.

Chart 6: US IPPs have bucked the trend and outperformed strongly in recent years

Recent US policy clarity has enhanced the appeal of US utilities. After the turbulence of pandemic-related demand swings and energy market volatility, the combination of predictable earnings, infrastructure modernisation, and an ongoing push toward renewable integration positions the sector to benefit from a lower rate backdrop. In this way, US utilities share many of the same rate-driven dynamics as European peers, demonstrating that interest rates remain a key lever shaping valuations on both sides of the Atlantic.

What about yield curve moves?

The relationship between utilities and the yield curve has been a key area of focus for sector specialists and generalists alike. As described above, utilities are traditionally seen as bond-like investments. When the yield curve steepens and long-term rates rise, those bond-like attributes lose some of their shine, as investors can earn higher yields from safer fixed-income assets. Conversely, when the curve flattens or inverts, typically signalling economic slowdown, utilities tend to outperform – benefiting from their defensive reputation and steady cash flows.

However, the impact is not uniform. Regulated utilities with inflation-linked pricing mechanisms or predictable returns can withstand steeper yield curves much better than those with no inflation protection or unhedged debt.

Conclusion

The interplay between interest rates, yield curve movements, and equity markets is complex, especially for a sector as capital-intensive as utilities. While rising rates generally increase financing costs and pose challenges, some utilities benefit from regulatory and inflation protection mechanisms which allow them to partially offset the negative impact.

In a shifting rate environment, active management can add real value by actively rotating across utilities sub-sectors that respond differently to monetary trends. By understanding the nuances of capital structure, regulation, and demand dynamics, active management can position a portfolio to capture opportunities and cushion risk as rate regimes evolve – turning sector complexity into a competitive edge.

We believe the outlook for utilities has brightened markedly now that the shocks of the past few years – COVID disruptions, energy market turmoil from the Ukraine war, and US policy headwinds – have eased. Moreover, the rising prospects of declining interest rates should translate into a strong tailwind for the sector that remains attractively valued despite all the positive drivers.

Finally, it is worth highlighting that the utilities sector has outgrown its image as a mere bond proxy, emerging as a key driver of the global energy transition. Electrification, surging power demand and the explosive growth of data centres have transformed utilities into growth assets rather than just income plays. As electricity becomes the backbone of modern industry and digital infrastructure, utilities now offer a blend of stability and long-term expansion that sets them apart from their traditionally defensive past.

Sources:

[1] Bloomberg, 26 June 2013 – 15 April 2015

[2] Bloomberg, 13 December 2021 – 12 October 2022

[3] Bloomberg, 6 November 2018 – 18 February 2020

[4] Bloomberg, 15 December 2021 – 2 October 2023

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to the future. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.