The case for owning value stocks today would seem to be compelling.

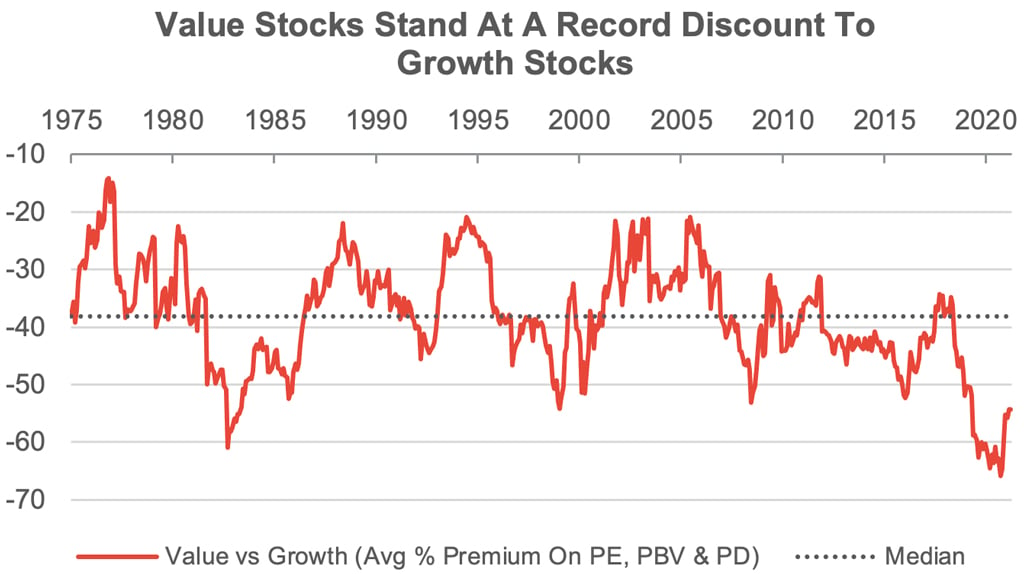

1. The gap in valuations versus growth stocks is wider than in 2000

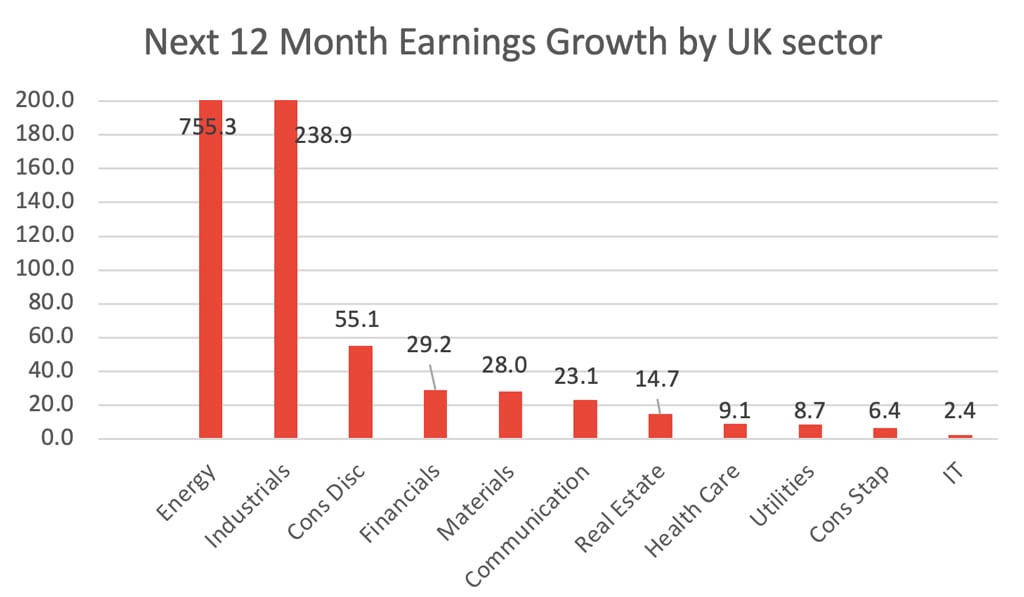

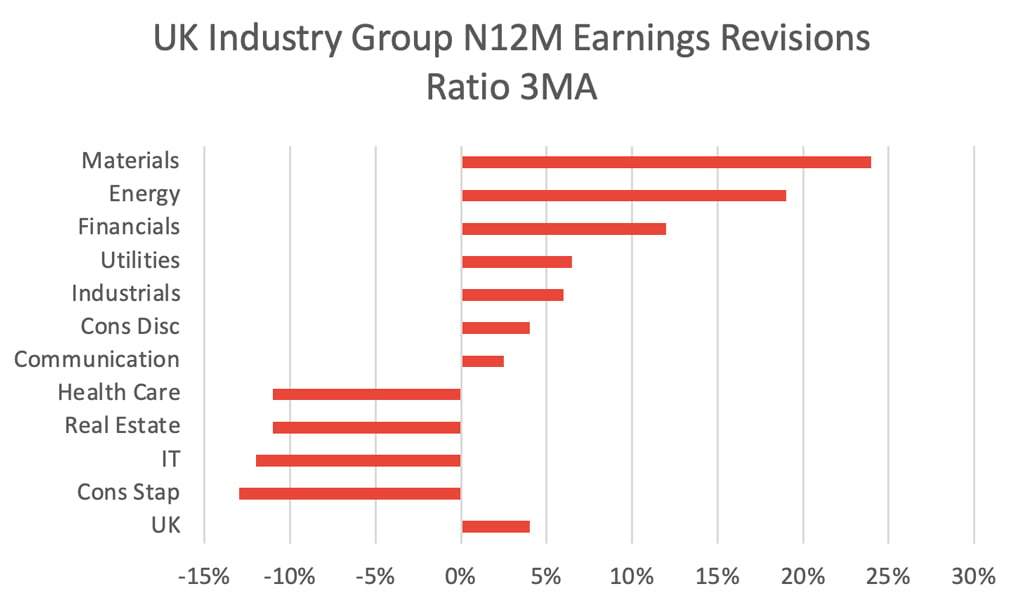

2. Value sectors offer the greatest earnings growth in the next two years

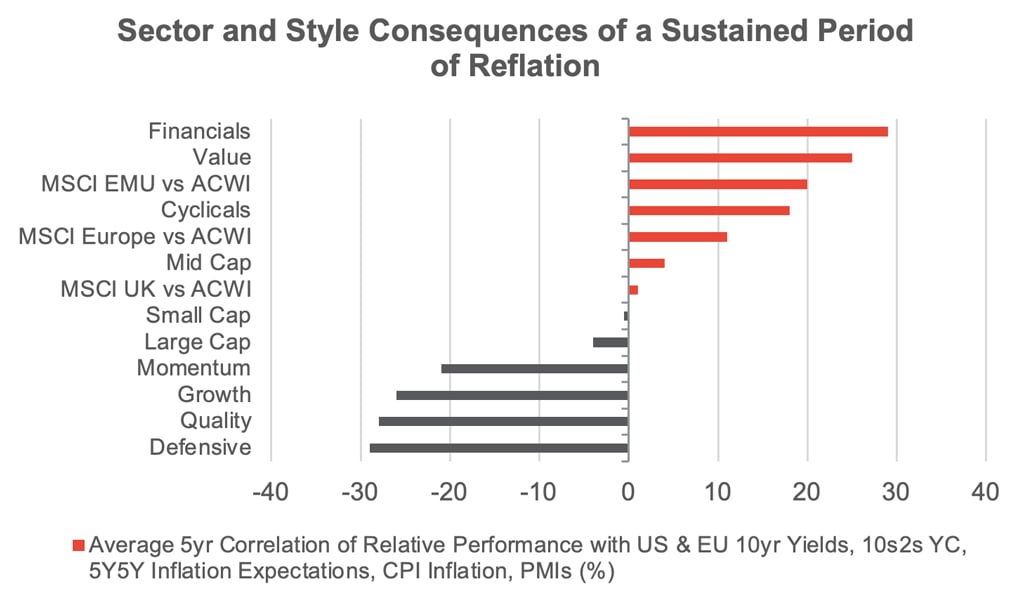

3. Value sectors offer one of the best hedges against inflation and rising bond yields.

Despite this, we are repeatedly told that most investors have no appetite for value stocks and are willing to stick with high quality and growth stocks despite the latter’s lacklustre performance over the last year. Many investors are hence making a deliberate choice to own expensive stocks with slow earnings growth over cheaper stocks with faster earnings growth – something that on the face of it seems hard to explain. In an efficient market, investors would alter their allocation to capture the better risk reward proposition that value stocks seem to offer and the fact that they are not doing this suggests that certain behavioural biases are over-riding logic. We offer some suggestions of what these might be.

Recency bias

The recency effect refers to the fact that people are more likely to recall information that is recent but also that is vivid and well-publicised. For example, when people in the United States are asked whether a shark attack or lightning strike is the more likely cause of death, a large number of people opt for shark attacks since these tend to be well publicised and post the film Jaws are easy to visualise. The reality is that you are 30 times more likely to die from lightning strikes than shark attacks (more people die from coconuts falling on their head than shark attacks!)[1].

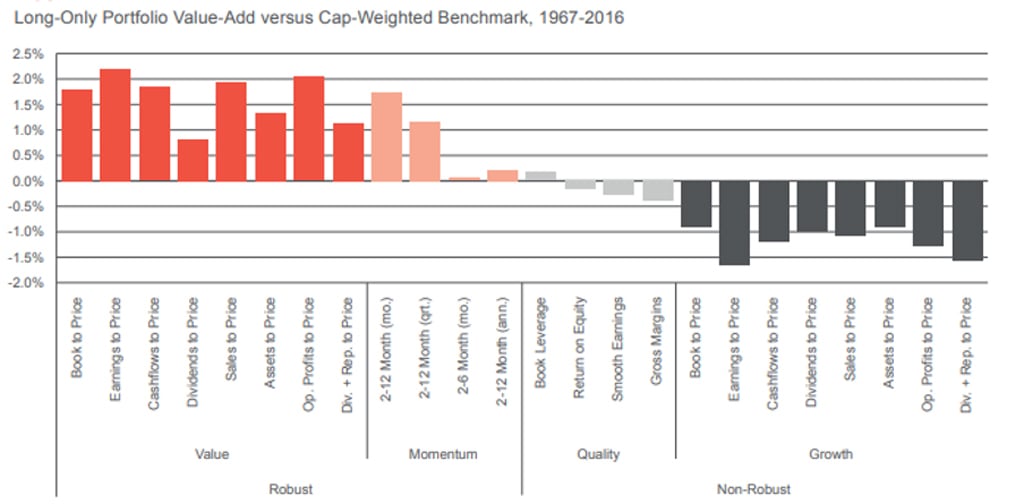

Within investing, there is a huge amount of empirical evidence to suggest that growth or quality stocks produce a return below that of a cap weighted benchmark and that value and momentum strategies produce excess returns (see table below for one such study).

Source: Research Affiliates, LLC, based on data from CRSP and Compustat.

When investors hear news stories of department stores closing it creates a form of recency bias that makes it hard for them to understand why a fund manager might be buying a retail stock. The attractions of growth investing are both vivid and well-publicised but so too are the myriad of reasons not to buy a value stock. We believe it is this recency bias which leads investors to ignore the long history of excess returns from value investing in favour of the more recent experience of high quality and growth stocks.

Herding

There is a great deal of evidence to suggest that human beings have evolved for social conformity and herding. An experiment by Eisenberger and Lieberman (2004) asked participants to play a computer game with two other players, throwing a ball back and forth. When the other players started to exclude the participant from the game, scientists noted that activity was generated in the anterior cingulate cortex and the insula, the parts of the brain which also feel physical pain.

In the world of investing, following a contrarian strategy like value investing generates the pain of social exclusion (as James Montier describes it, following a contrarian strategy is like having your arm broken on a repeated basis![2]). Thus, if you are a wealth manager/fund of funds etc and your competitors own mostly high quality and growth funds it takes an enormous amount of courage to diverge from them and allocate to value funds. As John Maynard Keynes stated, ‘Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally’. Thus, investors may forego the chance of a higher return and accept a lower return if it is likely that their competitors will also experience this lower return.

Loss aversion

Numerous experiments have shown that investors will give up a disproportionate amount of return in the search of predictability – a process known as loss aversion. In one such experiment, the author Shane Frederick asked participants several Cognitive Reflection Tasks[3] (CRT). Those that scored low numbers used the X-system of the brain (fast response) whilst those that scored high numbers tended to use the C-system and were more considered and logical.

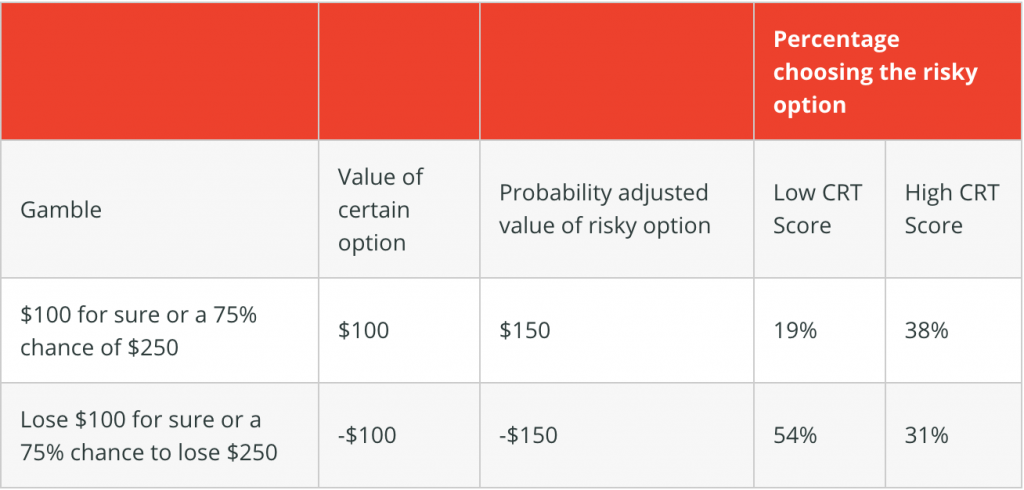

He then offered participants the choice between a certain gain/loss and a riskier option that had a better expected payoff. For instance, participants were offered a guaranteed $100 or 75% chance of $200 but with 25% chance of nothing (a risk weighted payoff of $150). When offered the choice between two profits, participants overwhelmingly go for the more certain outcome despite its lower expected return although those with low CRT scores showed greater preference for the certain option. When offered the choice between a certain loss of $100 and another option that gives the possibility of avoiding a loss (75% chance of loss of $200 and 25% chance of no loss), they will gamble despite the riskier option having a larger risk adjusted loss of -$150. In this case, their aversion to a loss meant they were willing to take a gamble that might mean they avoid it.

In the investing world, this loss aversion is one of the factors used to explain why value investing generates an excess return and high-quality investing generates a poor return. Investors equate a value stock with the risky option shown above and a blue chip, predictable stock with the guaranteed option but their aversion to losses means that they tend to overpay for certainty and hence reduce the returns of their investments.

Finally, it is important to realise that loss aversion is not a constant but varies over time. In March 2020, news about Covid-19 and associated lockdowns caused loss aversion to soar and meant investors were willing to pay a very high premium for certainty leading to an increase in the valuations of predictable stocks such as food and beverage companies. Conversely, they were willing to accept a huge discount to exit positions in stocks most likely to be impacted by lockdown policies such as banks and retailers.

Inertia/Regret

This refers to the fact that people feel regret about action and inaction in different ways and this is best illustrated with an analogy. Let’s imagine two fund managers, Sue and Jessica, work at the same firm in 2020 and that Sue owns a position in Tesla whilst Jessica owns a position in Exxon. As the news of Covid-19 emerges and the share price of Tesla starts to decline, Sue thinks about switching her Tesla into Exxon and eventually decides to make that trade. Jessica thinks about using the weakness in Tesla to sell Exxon and buy Tesla but eventually decides to take no action. A year later, Tesla has gone up tenfold whilst Exxon is unchanged – who do you think feels worse? The overwhelming likelihood is that Sue feels worse since without her action, she would have had a ten bagger in Tesla.

The fact that people feel deeper regret about taking an action that subsequently proved to be wrong than they do about taking no action leads to inertia and is one of the things that is often used to explain financial bubbles and elongated cycles. It seems reasonable to assume that investors who have been sitting in underperforming quality stocks and missed out on the initial gains of the rotation to value fear that they may switch now just as the value cycle peaks and would suffer huge regret. Knowing this, they opt for no action and stick with their quality stocks whilst hoping that the value rotation runs out of steam soon.

Short term bias and hyperbolic discounting

Not only can value strategies go wrong but they can take a long time to work and this has certainly been the case in the last decade when the underperformance of value has tested the patience of a saint. This means that to invest in a value strategy you need a long-time horizon which does not come naturally to human beings. When we are faced with the possibility of a reward, our brain releases dopamine which stimulates us and makes us feel good. Most of the dopamine receptors are in areas of the brain associated with the X-system (our fast system) and this make us favour instant gratification over a reward which that takes longer to occur.

McClure et al[4] investigated the neural systems that underlie decisions surrounding delayed gratification. For instance, when offered the choice between £10 today and £11 tomorrow, most people choose the immediate option. However, when asked to choose between £10 in a year and £11 in a year and a day, many of those who previously went for the immediate option now go for the second option even though the time difference between the two options is still one day. This effect, known as hyperbolic discounting, is our inclination to choose immediate rewards over rewards that come later, even when these immediate rewards are smaller. Hyperbolic discounting is not consistent across time which means that people might be willing to wait longer for rewards they already expect to receive in the distant future, while assigning a significant discount to small delays in rewards they expected to receive in the near future.

In investment terms, these means that investors are inclined to follow strategies which seem likely to pay off in the short term even at the expense of ones which might have a greater payoff, but which take longer to occur. Yet again, this tends to favour growth strategies which can have a very quick reward over value strategies which typically take longer to reward investors.

Conclusion

Value stocks appear to have most of the attributes that investors desire (cheap, earnings growth and upgrades, inflation hedge) and yet very few seem willing to exploit the opportunity being presented to them. We have suggested several behavioural biases that are plausible explanations for why investors seem unwilling or able to rotate in to value stocks, but we would finish by pointing out that this is not necessarily a low risk option. If professional investors look back in two years’ time and the cheapest stocks with the fastest earnings growth have substantially outperformed expensive stocks with slow earnings growth, they may have to face some very uncomfortable conversations with the clients who have missed out. Given this, taking some sort of position in value now seems like one of the best hedges against this future uncertainty.

Answer: the bat costs $1.05 and the ball costs $0.05. Many respondents answer $1 and $0.1 which is only $0.9 difference.

Unless otherwise stated, all opinions within this document are those of the UK Value & Income team, as at 15th April 2021.