As the prices of nearly everything have soared over the last year, the world’s major central banks have been assuring investors that this is just a temporary blip or as Jerome Powell, Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, had repeatedly said, inflation is just ‘transitory’. The Bank of England had also been singing from the same hymn sheet.

“The Committee’s central expectation is that current elevated global and domestic cost pressures will prove transitory.” [1]

For the moment, most investors seem to believe this narrative given that bond yields in most countries are several percentage points below the current levels of inflation (incredibly, 85% of US junk bonds now yield less than US CPI!) and, in many parts of the world, equities sport some of the highest valuations witnessed in stock market history.

The market has been remarkably trustworthy about these assurances given the poor forecasting records of the central banks.

All that said, given the fundamental factors in place that should support the demand for housing, we believe the effect of the troubles in the subprime sector on the broader housing market will likely be limited, and we do not expect significant spillovers from the subprime market to the rest of the economy or to the financial system,”

Ben Bernanke in May 2007

” The Federal Reserve is not currently forecasting a recession .”

Ben Bernanke 10 Jan 2008 (it was later determined the recession had started in December 2007)

” The GSEs are adequately capitalized. They are in no danger of failing. “

Ben Bernanke July 20, 2008 (the GSE’s were placed into conservatorship in September 2008)

It should also be obvious that central banks are talking their own book as they need the current levels of inflation to be transitory having painted themselves into a corner by blowing one of the biggest asset bubbles of all time. This now requires continuous money printing to stop it from collapsing and a sustained increase in inflation would put pressure on this strategy.

[1] Source: Bank of England

Past performance is not a guide to the future. The price of investments and the income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

The information shown above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice.

In the last few weeks, however, something appears to have changed. Firstly, as inflation figures have continued to surprise on the upside, central banks have been forced to admit that maybe it wasn’t going away. In the US, the year-on-year change in the CPI index was 5.4% in September 2021, whilst the producer price index (PPI – a measure of the prices that producers pay, and therefore a leading indicator of where consumer prices may be heading) change came in at 8.6%. The Bank of England’s new economist, Huw Pill, has said he would “not be shocked” to see UK inflation reach 5% or above in the coming months.[1]

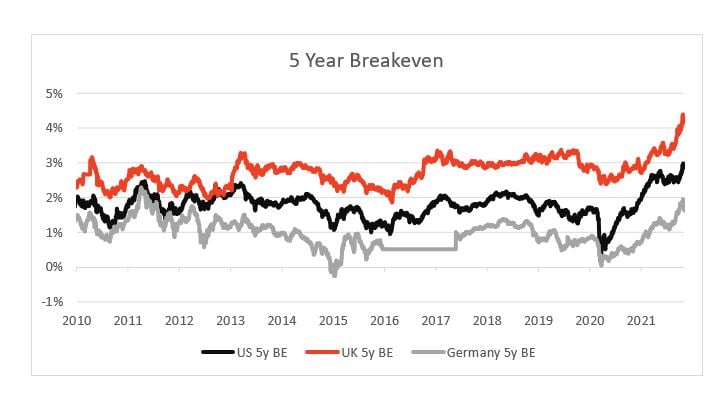

The idea that inflation will remain at elevated levels has begun to be reflected in market expectations of inflation as shown by the breakeven (chart below) which are at 11-year highs.

[1] BoE chief economist warns UK inflation likely to hit 5%, Financial Times

Past performance is not a guide to the future. The price of investments and the income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

The information shown above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice.

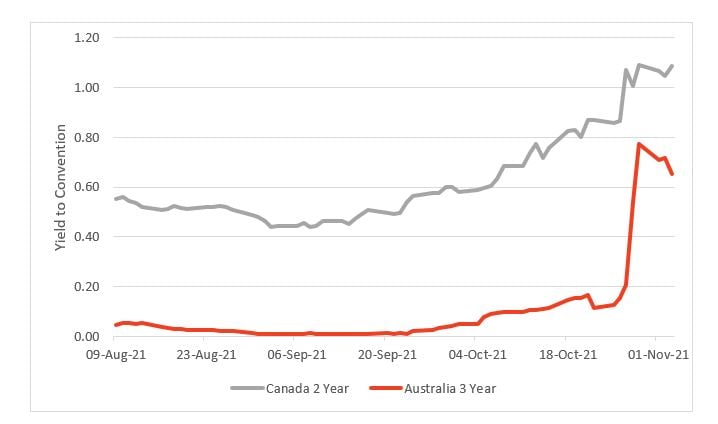

In some countries, central banks have actually started to reverse policy with the first being the Bank of Canada which recently announced the end of Quantitative Easing (QE) outright, which began November 1 2021 .It also moved rate hikes closer, with April 2022 now showing up as the expected date of a first increase. In response, the Canada 2-year yield spiked by 21 basis points, to 1.08%, having more than doubled over the past four weeks. Elsewhere, the Reserve Bank of Australia has ended its policy of yield curve control, becoming one of the first large central banks to act against a post-pandemic surge in prices saying that it would no longer try to keep the yield on three-year bonds at 0.1 per cent,[1] following a week of turmoil in short-term bond markets during which yields soared after the RBA declined to defend its cap. In the US, the Federal Reserve have announced that it will begin to reduce its massive $120bn a month quantitative easing programme by $15bn a month and Jerome Powell admitted that inflation is “running well above our 2% longer run goal”.

[1] Australian central bank tightens monetary policy to deal with price surge, Financial Times 2nd November 2021

Past performance is not a guide to the future. The price of investments and the income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

The information shown above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice.

The central banks are, however, walking a tightrope. Given the huge amount of leverage in the system, they know that even a small rise in interest rates runs the danger of tipping the global economy back into recession. In addition, it is very hard to see how they can aggressively reverse the course of current monetary policy, with nearly all asset markets at very elevated levels. Note that the Federal Reserve is not tightening but merely expanding its balance sheet at a slower pace despite inflation running above 5%. Meanwhile, the Bank of England also recently voted to leave interest rates unchanged and continue with their current level of quantitative easing despite their own economist’s forecast of 5% inflation in 2022. European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde said the European Central Bank is very unlikely to raise interest rates next year as inflation remains too low. They seem inclined to let inflation run hot rather than tighten too soon and this obviously leads to the risk of them being behind the curve and letting inflation spiral out of control.

Hope for the best, plan for the worst

Whilst we have no idea whether the current level of inflation will be sustained or transitory, we do know that current monetary and fiscal policy settings have historically been associated with rising consumer prices and therefore know it is a scenario that cannot be ruled out. We also know that an enduring period of inflation is not being priced into most asset classes. As the title of this piece suggests, we should hope for the best, but plan for the worst. Even if we believe that the chances of a sustained rise in inflation are low, we should consider the consequences of being wrong and these look significant to us given the elevated levels of asset prices.

This was a theme explored in a recent research paper[1] by James Montier at GMO in which he looked at which asset classes were the best store of value in the inflationary seventies. Whilst Montier himself doesn’t think that inflation is likely to be sustained he maintains that investors need to build portfolios that are robust against a range of outcomes because, like us, he acknowledges that it is always possible he could be wrong.

‘We have often talked about the need to build robust portfolios – that is portfolios that can survive multiple outcomes. This desire stems from Elroy Dimson’s excellent definition of risk as “more things can happen than will happen”. So, thinking through how to ‘inflation-proof’ a portfolio is always a worthwhile endeavour, even in the absence of a strong inflationary view.’

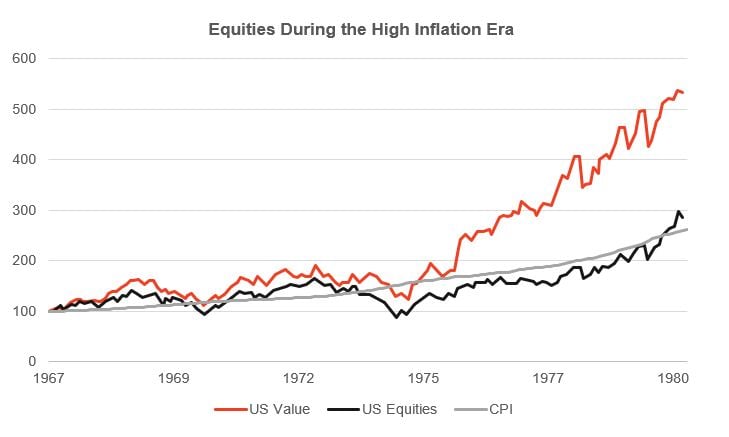

The paper finds that some of the asset classes which investors consider inflation hedges, such as Treasury Inflation Protected Securities or Commodities can be useful short-term inflation hedges but are less effective at preserving wealth in the long term. Conversely, asset classes such as equities can be a poor short-term hedge as demonstrated by the draw down in the early seventies but can still be a good store of value in the long term.

‘Our best recommendation is to buy true, real assets as a store of value. Foremost amongst these assets is obviously equities. They may make a terrible inflation hedge (as they did during the early 1970s), but over the long term they represent the businesses that charge prices and pay wages, so their cash flows should be real if these two elements are roughly matched. As such, they act as a store of value in the longer term.’

Within equities, however, the paper finds that holding value stocks is an even better strategy as the chart below demonstrates.

[1] What to Do in the Case of Sustained Inflation: What if We’re Wrong?

Past performance is not a guide to the future. The price of investments and the income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

The information shown above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice.

‘Of course, you can do better than simply buying equities. During the last bout of significant inflation, commodity equities were a good store of value (unlike the underlying commodities), and so were value stocks in general. Why? Effectively, you were buying cheap real assets. This is like being offered inflation insurance at a discount. So, if you are worried about inflation and looking for a store of value, or you are trying to build a robust portfolio that can survive lots of different outcomes, then buying cheap equities looks like a great place to start.’

The case for value

We acknowledge that it is not easy today to find an asset class which is inexpensive, let alone one which may also provide a hedge against an increase in inflation expectations. However, this is where a value strategy may be useful for two reasons.

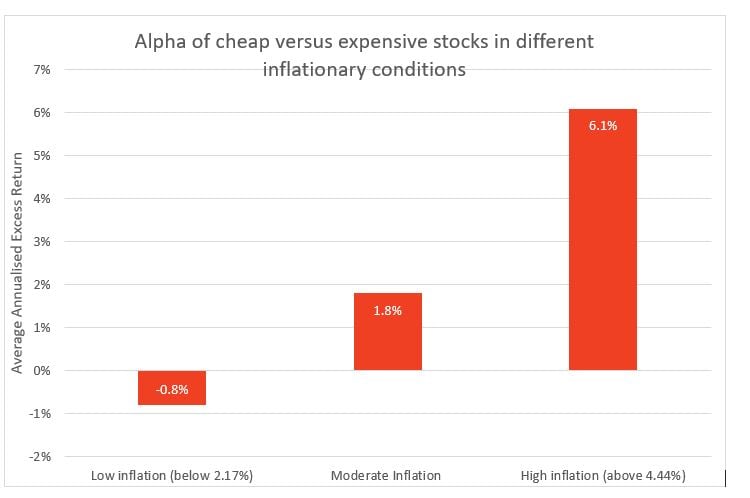

Firstly, we believe that low starting valuation is one of the best hedges against rising inflation. Value is one of the few areas that still looks cheap on an absolute basis and hence offers the potential opportunity to make positive real returns over the long term. This is also highlighted by the data in the chart below.

Past performance is not a guide to the future. The price of investments and the income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

The information shown above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice.

Since the average stock within the Temple Bar portfolio has an earnings yield of more than 10%, we believe our strategy has one of the best chances to deliver a long-term return that exceeds current rates of inflation. A negatively yielding bond, or an equity with a 2% earnings yield, is much less likely to do that.

Secondly, some of the core value sectors such as energy, materials and financials are those which have historically benefitted during an inflationary environment. Perhaps surprisingly, these sectors are also available at low starting valuations and hence potentially offer a cheap inflation hedge. Given the downside risk to so many asset classes in the event of a rise in inflation, we can see a role for a value strategy in most investors’ portfolios.

Unless otherwise stated, all opinions within this document are those of the RWC UK Value & Income team, as at 10th November 2021.