One of the most popular shows on the Discovery channel is ‘Deadliest Catch’, a reality series about the perilous voyages of Alaskan crab fishermen in the Bering Sea. The highly prized Alaskan king crabs, which the fishermen compete to catch, can command prices of up to US $90/lb, about twelve times the price of good quality beef. Now in its 18th season, the show follows real crews as they risk life and limb in some of the worst working conditions imaginable – ice cold seas, torrential rain, pounding waves and heavy machinery – in search of a bumper annual haul.

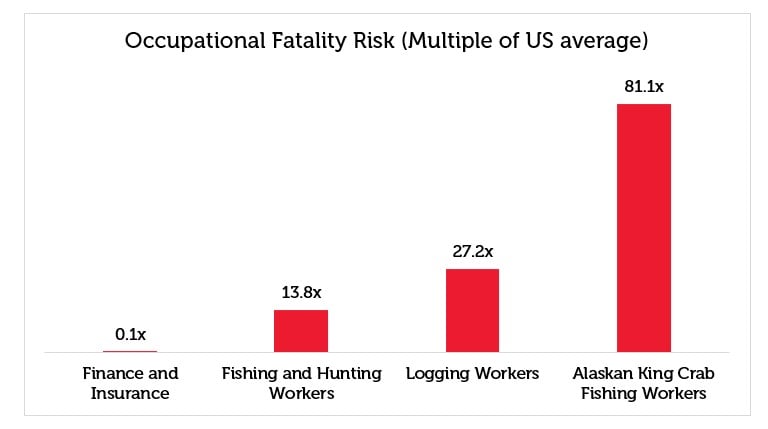

As the show’s title indicates, it is safe to say that Alaskan king crab fishing is one of the most dangerous occupations in the world. It has a fatality rate of 300 per 100,000 per year, about 80 times the US national average in 2022 (3.7 per 100,000), and about six times the average for fishing in general (50.7 deaths per 100,000, or 14 times the US national average).[1] Why on earth would anybody accept such occupational risks?

The answer, of course, is the money: for taking on such dangerous jobs, crab fishermen can command significantly higher pay than less risky jobs that match their qualification levels. For an average crew hand, a two-month season on an Alaskan king crab fishing vessel reportedly pays up to $50,000. This far exceeds what most of the fishermen – who on average have less than college degree levels of education – could earn elsewhere. One study [2] from 2018 compared the hourly wages of the off and on-season jobs of Alaskan crab fishermen, finding that, on average, for every $1 earned in an off-season role, they earned roughly $4 in season as fishermen. In fact, king crab fishing pay correlates so closely with danger that wages typically vary by month – with lower pay in the less dangerous summer season, and surging rates in winter.

This phenomenon, commonly termed ‘hazard pay’, is found across industries, and is intuitive to most people. Yet, many investors seem to have missed the memo.

What can investors learn from Alaskan crab fisherman?

Broadly speaking, investors are trying to earn a return that compensates them – or, ideally, overcompensates them – for the risk they are taking. Evaluating ownership of a company’s shares based purely on the perceived quality of the business, without regard to price, would therefore be illogical; it would be like looking at the risk of a job without asking how much it pays. By the same logic, who would ever take up king crab fishing in Alaska when a nice, warm cashier’s job is far less risky? Looking only through the lens of comfort without regard for compensation for being uncomfortable is not how we think in the real world, and should not be how investors think about their portfolios.

This is exemplified when it comes to how investors view the companies they own. If the top ten holdings in your portfolio give you a warm and fuzzy glow inside, we suggest that this should prompt concern rather than congratulation. Ask yourself why the market should pay you above average returns to own a celebrated outperformer. Surely, the warm and fuzzy glow should be something that you pay for in the form of lower future returns. In the same way, employees should expect to earn less in a warm regional sales office with free doughnuts and coffee than they would on the deck of an Alaskan fishing vessel in mid-December.[3]

If the top ten holdings in your portfolio give you a warm and fuzzy glow inside, we suggest that this should prompt concern rather than congratulation.

'Psychic returns' versus hazard pay

Academic research into this phenomenon has focused on the art world, based on the observation that, in aggregate, art investments yield lower average annual returns than other assets.[4] This had led academics to introduce the term ‘psychic returns’, the implied annualised return that an art owner will forgo to enjoy the benefits of owning fine art and having the pleasure of looking at it over time. It seems logical to us that there should be a cost to owning assets that bestow some kind benefit to investors (e.g. comfort or kudos) – a cost borne in the form of lower returns – compared to less comfortable or palatable alternatives.

By that token, if the top ten companies in your portfolio make you break out in a cold sweat, that may actually be a good sign: there may be a chance – if the price is right – to earn some premium hazard pay for your troubles.[5]

If the top ten holdings in your portfolio make you break out in a cold sweat, that may actually be a good sign.

For example, market ambivalence or aversion to a company or sector can sometimes translate into a significant discount to the intrinsic value of the business –what its long-term cashflows are truly worth. The chance to buy companies at this discount is generally what creates opportunity for long-term outperformance, and it is this opportunity that we as value investors search for every day. In fact, investing is likely an even better place to earn hazard pay than on a king crab fishing boat. Whilst fishermen cannot diversify away their risk of life and limb as they seek higher pay, investors can hold several companies at a time: each position should individually provide ample compensation for their risks while diversifying our worst-case exposure, and retaining the attractive payoff opportunities.[6]

Assessing the hazard pay premium

Of course, by the same token, investors should not fall over themselves to take incremental units of risk for their own sake. After all, leaving your office job to work as a crab fisherman for only an extra US $1 a day is probably an unwise decision. What is important to appreciate, however, is that there is a dividing line between job risk and job pay – or, in the markets, company quality and company price. Thinking carefully about being sufficiently well paid for the risk you are taking is the key. A Maserati is clearly a higher quality car than a Vauxhall, yet a Maserati at £50m is clearly a worse deal than a Vauxhall at £10.

So, the next time that you look at your portfolio, stop and think: does this company and industry make me feel safe, secure, and rather clever? Or does it bring feelings of discomfort, insecurity and a fear of looking stupid in front of your peers? If the former, why should you be getting paid more to own it? If the latter, it is likely that many other investors are quite happy to let you earn the hazard pay premium that can come from accepting the discomfort that they won’t.

Sources:

[1] Finance and insurance, you’ll be pleased to know, is one of the lowest risk professions, with a fatality of just 0.2 per 100,000 workers per year (source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries, 2022)

[2] Lavetti, Kurt « The Estimation of Compensating Wage Differentials: Lessons from the Deadliest Catch », Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, Vol. 38, No. 1, (Jan. 2020)

[3] Adjusting to equalize for qualification-equivalent roles

[4] Atukeren, E. and Seçkin, A., 2007. “On The Valuation of Psychic Returns To Art Market Investments”. Economics Bulletin, 26(5), pp.1-12.

[5] It was this insight that made the career of junk bond king Michael Milken, and the modern high yield market. He observed that investors that shunned sub-investment grade bonds at any price were underperforming the lower-rated debt. While there were more defaults in junk bonds, the lower initial prices overall more than compensated for the increased risk.

[6] Not to mention the much more comfortable working environment that even the most hardened value investors endure relative to the high seas of Alaska

[7] Adobe Stock Image, sourced 13.05.2024

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.