The Grave Dancer

In late 2007, at the height of the real estate mania gripping the USA, the famed real estate investor Sam Zell struck a deal that is still upheld today a masterclass in timing. In August 2007, about a year before real estate prices began to implode, Zell sparked a bidding war for his commercial property REIT, Equity Office Properties. His eventual buyer was the private equity giant Blackstone, who bought the company in a blockbuster deal valued at $39bn, enabling Zell and his happy shareholders to neatly cash out of the company he had spent 30 years building, in a deal which was, at the time, the largest buyout in history.

Zell was a veteran of US real estate investing, and carried the moniker of ‘Grave Dancer’, which he earned after penning an article outlining his approach to buying cheap, distressed assets, a playbook he employed many times on his road to success. As well as his long record of exceptional real estate investing, Zell was famous for his penchant for communicating his investment philosophy in quirky ways: t-shirts he would distribute to IPO roadshow attendees, music boxes he sent to business partners as gifts, and cartoons which captured key tenets of his investing style[1].

One such cartoon illustrates one of his favourite maxims. It depicts two boxers in a ring, facing off. One is a huge, hulking man with rippling muscles whilst the other is a skinny, bespectacled man about half his size. What the latter does have, however, is a loaded rifle – and a cheeky grin on his face. The caption reads: “Be a risk taker, however define risk by your own terms”.

In our view, this principle resides at the core of disciplined investing, empowering the patient, diligent value seeker to scour the globe for compelling risks to take – and compelling rewards to reap.

Find the (non-smoking) gun

Often, investors identify obvious risk – the prospect of having to fight a seven-foot tall, muscle-bound punching machine – whilst failing to identify the less obvious risk mitigators, like having a fully loaded shotgun hidden in your corner of the ring. Considering one without the other ignores a fundamental element of any basic risk analysis, but is sufficient to drive plenty of irrational investor behaviour we regularly see in the market.

The first such behaviour is the summary rejection of nose-wrinkling corners of the market, where red flags fly and warning lights flash; however, those untrodden corners often create fertile hunting grounds for those willing to look. Take, for example, a recent area in which we have been investing: South Korean banks.

For a multitude of reasons, just uttering the phrase “South Korean banks” can induce for many investors at best gaping yawns, if not spine shudders and cold sweats. The first reason is simply the country of origin: South Korea has long had uninspiring corporate governance – exemplified by the family-controlled Chaebols – as well as strangely frequent periods of political instability, which has led to typically lower valuations for South Korean companies than developed peers.

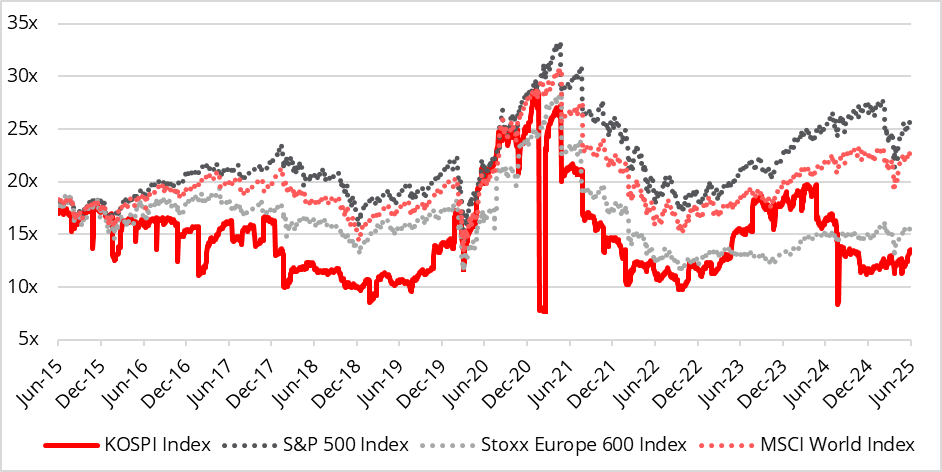

Chart 1: Price / earnings ratio of major indices, 2015 – 2025

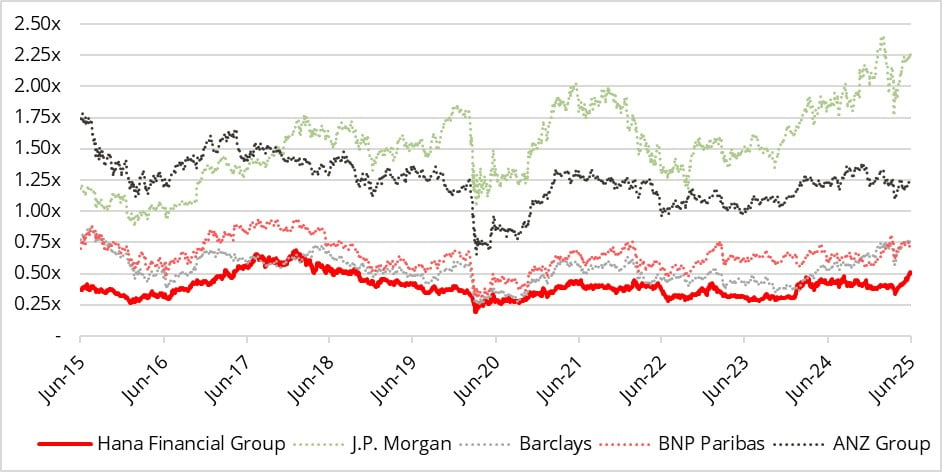

In addition, many “quality-first” investors tend to shun banks, viewing them as sprawling, inscrutable machines with timebombs buried deep within their balance sheets, just waiting to go off. In addition, many global investors were burned by South Korean banks during the Asian financial crisis in 1997, which set off a wave of government-induced restructuring and investor losses. Combining these factors has seen valuations for major South Korean financial institutions stumble along at levels far below those of their international peers that are often undervalued themselves. By way of example, below is the price-to-book ratio for a sample of global banks, compared to that of South Korean bank Hana Financial Group.

Chart 2: Price / book ratio of major global banks, 2015 – 2025

However, in our view, this nose-wrinkling is like focusing on the physique of the scrawny boxer in the blue corner – but totally ignoring the automatic weapon at his disposal.

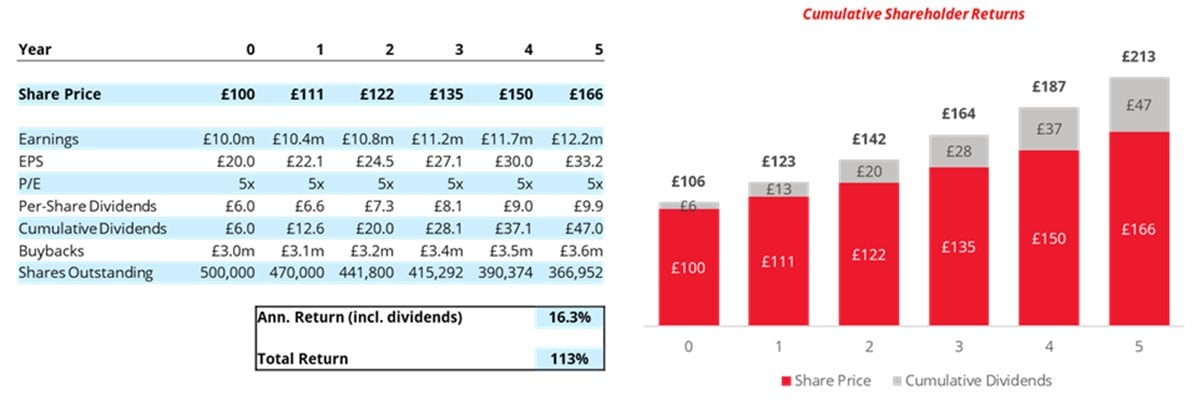

Take, for example, the poor valuation of South Korean companies, and how that has led to weak prices for the major domestic banks. Whilst it is true that share prices have barely budged in the last decade, what this analysis fails to recognise is that the companies behind those share prices have nonetheless delivered consistent growth over time, with assets, net interest income, and per-share earnings all compounding steadily higher [2]. The upshot is that these businesses have been getting cheaper and cheaper over time – and all the while demonstrating, with consistent growth and profitability, that they are worth more than their current meagre valuation. Now, we hear you argue, it is all very well that these companies are getting technically cheaper over time; but if the market price of their shares is not budging, how does that help me? This is a perfectly valid rebuttal – but not when a company allocates its blossoming piles of cash to create their own destiny through meaningful dividends and cheap buybacks. Which, as you may have guessed, is the case today for the South Korean banks.

Inspired by the success of Japan’s attempt to enforce better governance and capital efficiency standards for listed companies, South Korea’s Financial Services Commission launched a “Corporate Value UP” strategy in early 2024. Taking a leaf from Japan’s book, the programme urged Korean corporates to set out plans for increasing shareholder value, with the encouragement of higher dividends and buybacks where appropriate. Indeed, the new South Korean president ran on an explicitly pro-shareholder-interest ticket, and has already pledged a review of Korea’s dividend tax regime to encourage corporations to disburse more cash to shareholders. To the trained ear, the sound of a gun being loaded can be heard.

Indeed, our Korean bank holdings needed no additional encouragement in this arena, with strong cash yields – and the promise of higher payouts over time – as well as the initiation of substantial buybacks at eye-wateringly low prices: think price-to-earnings ratios in the 3x – 4x range (i.e. buying shares at an earnings yield of 25% – 30%) and price-to-book ratios of less than 0.4x3. Repurchasing shares at such low levels, whilst paying rising dividends and growing revenues, points to a strong likelihood of robust shareholder returns – even without any rerating of the share price.

Chart 3: Illustrative return with dividends, buybacks and no rerating

The litany of other initial nose-wrinkle criticisms can also be overcome with further analysis. Yes, South Korea has struggled in the past with corporate governance, but the Value UP program is a clear sign of progress on this issue, as is the fact that the pandemic caused a seismic shift in ownership patterns. Since 2018, the number of South Korean retail investors invested in domestic companies has ballooned from 5.0m to 14.2m [3], meaning that minority shareholder rights and improved returns are now serious voter issues that rank high on the political agenda.

In addition, whilst the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis was painful and left deep scars for foreign investors, it actually worked to make many financial systems more stable and consolidated – and hence more profitable and robust – through the cycle. For example, in South Korea, the government ordered the weakest banks to be absorbed by the strongest, and those banks somewhere in between to merge amongst themselves, creating a consolidated oligopoly that remains healthy, stable, and profitable. As we have also pointed out before to those who systematically shun banks as investments, the long-term bankruptcy record of global banks is, in fact, much better than many other sectors: the cumulative default rate for banks is 5.3% over a ten-year period, compared with 11.6% for healthcare, 24.1% for retail, and 26.2% for durable consumer goods [4].

We will continue to use these observations – simply considering the presence of a loaded gun in the ring – to bet heavily on the skinny guy.

Bet the fight, not the fighter

The same mistake is also made in the opposite direction. Many investors are quick to observe the fantastic economics and market positions of specific companies, thus noting that their boxer is a decorated champion with biceps the size of his head. Often, however, they fail to understand the question being asked of them, as he squares up to a scrawny accountant with an Uzi: it is not who is the better boxer, but who will win the fight. If you buy a premium company, but pay a premium price, your outcomes may not be determined by the strength of your fighter, but by the odds you accepted on him emerging victorious. If your premium company begins to be priced at a more reasonable valuation, then you are going to lose money, almost independent of how good a performance it is able to turn in.

A good recent example of this is the Danish healthcare company Coloplast, which is an undeniably high-quality operation. Returns on invested capital have averaged more than 30% for the past 20 years, and gross margins are routinely north of 60%. Yet, if you paid 55x trailing earnings for their shares in 2021, you would have lost 50% of your money – despite the fact that revenues have grown by over 45% since then, and per-share diluted earnings are up by 14% [5]. But all of that hard corporate effort has been squandered on those investors who ignored the shotgun in the opposite corner, over-egging the odds for their fighter and wildly overpaying for what they assumed was a sure-thing bet that they couldn’t lose. Today, that fine company is valued at 23x trailing earnings, a valuation that still seems to be on the high side of reasonable from where we sit. With such aimless enthusiasm, Coloplast’s investors have enjoyed effectively no total return since 2018 (1.95% in total with dividends reinvested), hard to believe when observing that revenues are 64% higher over that time, and per-share earnings are up 24% [6].

*********

Although we would no doubt enjoy spending our days trying to find prize fighters – companies with the best business models, defensive moats, and undeniable quality – that is not the task with which we are presented. Instead, we must handicap the fight in front of us – buying the most attractive investment opportunities, as measured by both corporate quality and the prospects of substantial quantitative returns – and focus on delivering superior investment performance over time. To that end, we are consistently delighted to find arenas where apparently weaker boxers are assumed to have no hope of surviving – but where spectators seem to have failed to notice the gun at the fistfight. Where the odds are right, we will be lining up to place those bets.

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to the future. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.

Sources:

[1] Due to a lack of talented comic artists on staff, our investors should expect no such similar treatment.

[2] Bloomberg, July 2025

[3] Korea Securities Depository, November 2023

[4] Moody’s Default Trends – Global, February 2024

[5] Bloomberg

[6] Bloomberg, 30 June, 2025