Blockbusters and buyouts

As career moves go, it’s certainly an unusual one. In 1969, a newly-minted Harvard Medical School graduate abandoned his promising career as a doctor to pursue his true passion: writing novels. As it turned out, this was a wise choice. That graduate – Michael Crichton – would go on to forge a highly successful career, churning out a string of famous novels. One of his books was catapulted to huge fame when it was immortalised in 1993 as a Steven Spielberg movie classic: Jurassic Park.

In the epic film, where lab-created dinosaurs roam free on an island-resort-gone-wrong, one scene is particularly memorable. In a storm, the park’s electric fences lose power just as our hero, palaeontologist Dr. Alan Grant, is sitting in a Jeep outside the Tyrannosaurus Rex enclosure – with two children in the car with him. Inevitably, the dinosaur dramatically escapes, flipping the car as it searches for an easy meal. Grabbing one of the children and standing perfectly still before the bellowing dinosaur, Dr. Grant delivers an iconic line: “Don’t move. He can’t see us if we don’t move” [1].

Those who have read my previous blogs posts will know that I am an advocate of learning important investment lessons from all forms of art, including books, TV shows, and movies. In this case, however, I think that one cohort of investors – our cousins in private equity – have learned perhaps the wrong lesson from this film, and from this line in particular. In Private Equity Park [2], their approach to valuation and volatility is a warped version of Dr. Grant’s famous line: if you can’t see it, it doesn’t move.

The illusion of stability

Ordinarily, when an investor wants to know the current market value of their investments, they check the listed price of their assets. Not so in private markets. Here, investors get a periodic and often lagged valuation concocted by an opaque internal process undertaken by the manager [3] rather than via a market of buyers and sellers setting a clearing price. This process is understandable – after all, they have to put a number on the investments somehow. What is perhaps less forgivable is the claim [4] that, as a result of this process, private investments are more stable and less risky asset classes – with risk often conflated with volatility – when compared to the daily price changes in public markets.

To this assertion, we must object.

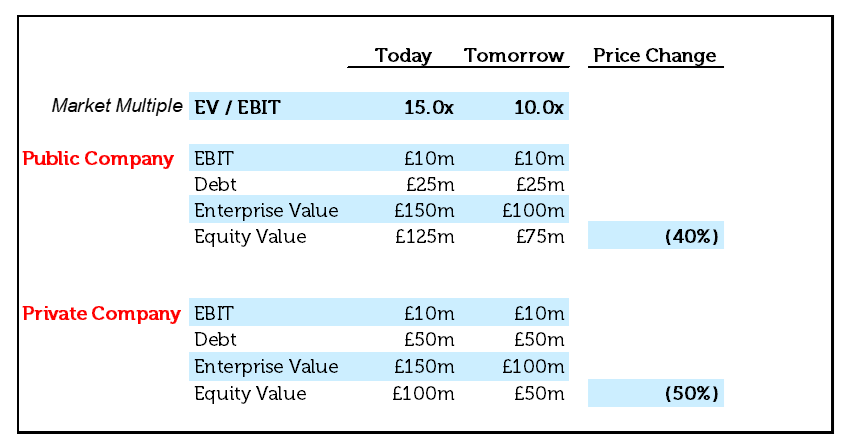

Simply because one cannot see valuations of private companies change does not mean that they do not move in lockstep with public peers. After all, one cannot forget the “equity” part of private equity: if they are truly buying operating companies, as we do in public markets, why would the value of those companies not simply move alongside their listed peers? Moreover, private equity-owned companies typically carry larger amounts of debt [5] than their public equivalents, meaning that, all else being equal, their equity valuations should swing more than those of listed companies:

As a result, claiming that the value of your companies is more stable than public equivalents simply because they are unlisted is pure fantasy (vocal critics have termed it volatility laundering). The persistence of such claims, despite many in the industry pointing out the obvious flaws, is a reflection of the eagerness of investors to see a smooth chart, rather than a lumpy one, a mindset that seems to us to be prevalent amongst many allocators today.

It’s the destination, not the journey

Whilst we certainly endorse the view that investors should ignore day-to-day volatility and focus on the long-term compounding of their capital, we believe that the way to do this is simply by being more willing to tolerate short-term volatility. In our view however, it is not done by paying extremely high fees to managers to employ huge leverage – often supplied by the credit arms of their own firms, who are in turn charging high fees to their investors – to buy small companies and then only report to you their (highly subjective) valuations at various protracted intervals. Impatience is not cured by avoiding anything that requires patience.

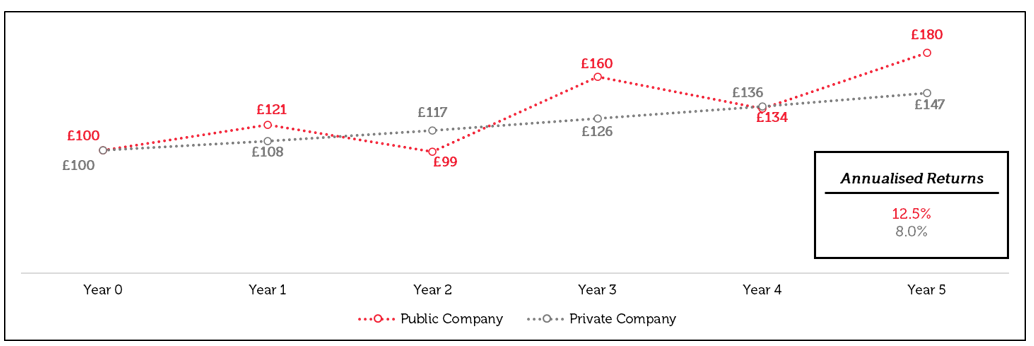

As we have argued in the past, we believe that public markets can offer better investment opportunities than those available to private equity investors, and the fact that the market value of our portfolio companies bounces around every day does not change that. What matters for investors with a long-term focus is simply how much capital they end up with, compared with how much they put in, and how long it takes them to grow that amount of money. What private markets are selling – at a steep price – is enforced long-term thinking. If investors think they can develop this ability on their own, they can save themselves a 2% management fee and possibly earn a better return by turning to public markets.

We would urge allocators with private equity investments – who are to some degree self-selecting as long-term investors – to acknowledge to themselves that if they are confident in the long-term prospects of the intrinsic value of their businesses, it does not matter whether the market prices for those businesses swing on a daily or weekly basis. What matters is the potential to buy something for substantially less than it is worth and to sell it, years later, for its true value:

The patience premium

Overall, what public markets offer is fundamentally no different to what investors are accessing in private equity wrappers: ownership of stakes in businesses, the chance to benefit from the growth and success of those businesses, and the talent of their executives. Public markets also tend to offer better liquidity, less leverage, greater transparency, access to larger companies, and all at typically lower prices – if investors are willing to be as patient as private options enforce. After all, corporate valuations are no dinosaurs: even if you can’t see them, they move.

Sources:

[1] For those curious, Tyrannosaurus Rex could probably see motionless prey perfectly well. However, it is here that Crichton’s attention to detail is magnificent. The book relays that, where the park scientists were unable to replicate dinosaur DNA, they used frog DNA as the next best thing, a kind of nucleic acid stopgap. As it turns out, some frogs do indeed have difficulty focussing on motionless prey, a detail that Crichton worked cleverly into the storyline of the novel, and which became a memorable line from the film

[2] An island where gilet-clad private equity investors run from the EBITDAsaurus and the PIKodocus

[3] Which some sceptical commentators might equate with marking your own homework

[4] Such as can be found on the websites of many large PE firms (https://www.blackstone.com/en-emea/pws/essentials-of-private-equity/, https://www.kkr.com/alternatives-unlocked/private-equity#2)

[5] https://verdadcap.com/archive/explaining-private-equity-returns-from-the-bottom-up?rq=leverage

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.